Introduction – Risk Transfer Generally

Construction is risky business. Owners’ risks include delays, contractor insolvency, financing issues, differing site conditions, and defective design and/or construction. Contractors risk jobsite injuries, disputes over alleged defects in the work, labor shortages, material cost escalation, project impacts outside their control, as well as lower-tier defaults for financial and other reasons.

Owners and contractors use a variety of techniques and products to mitigate and transfer risk. The first is contract language including provisions requiring indemnification, additional insured status and clauses waiving consequential damages or limiting liability altogether. A second is insurance. This includes first-party coverage (think protecting your own stuff) like property insurance and builder’s risk insurance. It also includes third-party coverage (think defensive coverage protecting you from the claims of others) such as Commercial General Liability insurance, Professional Liability insurance, Owner’s and Contractor’s Protective Liability Insurance, and Owner Controlled or Contractor Controlled Insurance Programs. A third method of risk mitigation is through the purchase of a surety bond, such as a Payment and Performance Bond.

This paper examines two (2) of these products, the almost universal Commercial General Liability (CGL) policy and the Performance Bond. Although both products sometimes respond to the same losses, their differences are critically important to understand. Specifically, we will look at the significant differences between these two (2) products, and how each responds to a jobsite loss.

The Commercial General Liability Policy

There may be no insurance document more ubiquitous in the construction industry today than the CGL policy. Everybody has one, and when something goes wrong on the site or on a completed project, it’s often the first place to look for insurance coverage. But simultaneously, few insurance documents are the source of more confusion and consternation (including the ultimate extension of consternation – litigation) among insureds, practitioners, and courts than this 100-plus page document.

Part of this confusion stems from the fact that CGL policies are not specifically designed for the construction industry. They provide liability coverage for all types of businesses, from manufacturers to service providers. These policies typically carry limits of $1MM or $2MM and are an insured’s primary defense against claims of “bodily injury” or “property damage.” CGL policies have become quite standardized over the years and most often adopt the standard language of the Insurance Services Office, Inc.

Businesses typically supplement the protection provided by the CGL policy with an umbrella or excess policy. Unlike CGL coverage forms, umbrella policies vary significantly among individual insurers. Umbrella policies can either “follow the form” where the umbrella policy provisions simply “drop down” and adopt the underlying CGL policy terms, conditions and exclusions, or the umbrella policy can have its own independent terms. An excess policy simply provides additional limits of insurance to cover the same exposures insured against in the primary or underlying policy, usually providing coverage for the “ultimate net loss” in excess of the primary policy’s coverage.

On a very high level, it is critical to remember that a CGL policy is defensive in nature. It responds to defend the policyholder against claims of others. These claims can, and many times do, include claims of defective workmanship and negligent construction in jurisdictions in which those claims have been held to constitute an “occurrence” for which the CGL policy provides coverage.

Duty to Defend Versus Duty to Indemnify

A CGL policy affords policyholders two overlapping, but distinct forms of protection – the insurer’s duty to defend its insured and its duty to indemnify. Both are extremely valuable. The duty to defend is generally significantly broader than the duty to indemnify and is triggered when the allegations or claims against the policyholder potentially or arguably fall within coverage. Indemnity is different. To trigger the carrier’s duty of indemnity, the allegations or claims must actually be covered, not just potentially covered.

The Triggering Event and Which Policy Responds

CGL’s are occurrence-based policies. This means that the policy in place at the time the loss occurred will respond to the claim. This is different from claims-made policies, like professional liability policies. Those policies respond based upon the time the claim is made against the policyholder and reported to the carrier.

Many times the date of loss is not clear. This is particularly true for progressive losses where the injury or damage worsens over time. Some typical examples are: (i) Curtain wall failure resulting in condensation and water intrusion that damages a building’s components over time; (ii) Wastewater treatment plant concrete cells that progressively move and crack over several freeze-thaw periods; and (iii) Pavement that gives way due to the gradual loss of supporting subgrade.

As a result, courts have developed several tests to determine when a policy is triggered. These are:

Exposure: When the claimant is exposed to conditions that cause damage (whether or not damage actually occurred in policy period).

Injury-In-Fact: When actual damage occurred during policy period.

Manifestation: When damage becomes apparent.

Continuous/Triple Trigger: All of the above.

Although an in-depth discussion of these theories is outside the scope of this presentation, policyholders are advised to put all potential CGL carriers on notice once they become aware of a loss or claim. Further, as more insurers have added endorsements that restrict and, in some instances, exclude coverage for continuous or progressive damage that began before the policy’s effective date, policyholders are advised to be familiar with all endorsements as well as the basic insuring agreement.

A CGL Claim Walk – Through

An example is probably the best way to explain how a CGL applies to a common loss in our industry. Although subject to infinite variations, the classic CGL claim is for damage caused by the defective work of a subcontractor. Defective work of the named insured is most often excluded. In our example, a roofing subcontractor improperly installs a roof, which leaks and damages other work. The general contractor is held responsible for this damage under its contract with the owner, and immediately notifies its CGL carrier of the loss. The general contractor then hires a different subcontractor to perform remedial work on the roof and other subcontractors to repair the other work that was damaged by the leakage. This damage to items other than the roof itself is typically described as resultant or consequential damage.

First, an insured must determine if an “occurrence” has taken place. An “occurrence” is usually defined as “an accident, including continuous or repeated exposure to substantially the same general harmful condition.”

States differ dramatically in how they address whether or not construction defects meet this definition. Although states are highly nuanced in how they conduct this analysis, there are three (3) major schools of thought:

- Defective or negligently performed construction work is not an “occurrence,” even if the poor workmanship was performed by a subcontractor. This is by far the minority position. At this time, only Kentucky, Ohio, Oregon and Pennsylvania have adopted this position.

- Defective or negligent workmanship that causes damage to property other than the defective work itself, or other parts of the construction project, meets the definition of “occurrence.” Under this method it is much more difficult for general contractors or construction managers to obtain coverage, as the entire construction project is considered their work. For subcontractors, the hurdle is much lower as their scopes of work are much more limited.

- Unintentional defective or faulty workmanship meets the definition of “occurrence” as the contractor did not intend the resulting damage. Courts employing this analysis focus on the policy’s exclusions to determine whether or not there is coverage.

The next step for the policyholder is demonstrating “property damage.” The CGL policy defines “property damage” as:

- Physical injury to tangible property, including all resulting loss of use of that property. All such loss of use shall be deemed to occur at the time of the physical injury that caused it; or

- Loss of use of tangible property that is not physically injured. All such loss of use shall be deemed to occur at the time of the occurrence that caused it.

In most construction defect cases the existence of “property damage” is not difficult to prove and courts do not come to drastically different conclusions. “Loss of use” can be used effectively to trigger coverage where the tangible damage to property is to the work itself and excluded.

Once the policyholder has made out a prima facie case for coverage, the burden shifts to the carrier to establish the applicability of any policy exclusion. Insurers typically raise three (3) exclusions found in the standard form CGL policies to defeat coverage in construction defect cases: j. Damage to Property, l. Damage to Your Work, and m. Impaired Property. If the insurer establishes the applicability of an exclusion, the burden shifts back to the insured to establish any exception to the exclusion provided by the policy.

The Damage to Property Exclusion

Insurers argue that Exclusion j. Damage to Property excludes defective work constructed by an insured or any of its subcontractors. This exclusion states:

This insurance does not apply to:

Damage to Property

‘Property Damage’ to:

* * *

(5) That particular part of real property on which you or any contractors or subcontractors working directly or indirectly on your behalf are performing operations, if the ‘property damage’ arises out of those operations; or

(6) That particular part of any property that must be restored, repaired or replaced because ‘your work’ was incorrectly performed on it.

* * *

Paragraph (6) of this exclusion does not apply to ‘property damage’ included in the ‘products-completed operations hazard.’

Damage to Property only applies to losses that occur when the work is ongoing. Paragraph 5 of the exclusion only applies when the contractor or subcontractor is “performing operations” and Paragraph 6 does not apply if the work is complete or has been put to its intended use (the definition of “products-completed operations hazard”).

It is also important to note that this exclusion applies only to “that particular part” of the property where the work was incorrectly performed. By way of example, where a subcontractor defectively installs a curtain drain and this causes the entire septic system on a home to fail, the exclusion would exclude the cost of repairing or replacing the curtain drain, but not the cost of the alternative waste disposal system made necessary by the failure of the curtain drain. Put another way, it is arguable that this exclusion does not reach resultant or consequential damage.

In our example, this exclusion does not bar coverage, as the loss (the leaking and resultant damage to other property) occurred after work on the roof was complete.

The Damage to Your Work Exclusion

Exclusion l. Damage to Your Work, states that the insurance does not apply to:

Damage to Your Work

‘Property damage’ to ‘your work’ arising out of it or any part of it and included in the ‘products-completed operations hazard.’

This exclusion does not apply if the damaged work or the work out of which the damage arises was performed on your behalf by a subcontractor.

This exclusion is quite broad and is not limited to on-going operations. The exception to the exclusion, however, is equally broad as it covers damage caused by a subcontractor. In our example, the defective work was performed by the insured’s subcontractor. As such, coverage is not excluded.

The Damage to Impaired Property or Property Not Physically Injured Exclusion

Insurers also argue that Exclusion m. Damage to Impaired Property or Property Not Physically Injured precludes coverage for defective work. This exclusion states that the CGL policy does not apply to:

Damage to Impaired Property or Property Not Physically Injured

‘Property damage’ to ‘impaired property’ or property that has not been physically injured, arising out of:

(1) A defect, deficiency, inadequacy or dangerous condition in ‘your product’ or ‘your work’; or

(2) A delay or failure by you or anyone acting on your behalf to perform a contract or an agreement in accordance with its terms.

This exclusion does not apply to the loss of use of other property arising out of sudden and accidental physical injury to ‘your product’ or ‘your work’ after it has been put to its intended use.

This exclusion is extremely complicated. It is meant to preclude coverage for loss of use of property that has not been physically injured, other than its incorporation of defective work or materials. The most important point to remember with respect to the exclusion is that it only applies where simple replacement of the work or product itself—without anything more—restores full use. In the construction context, almost every loss involving defective work requires removing and replacing good (non-defective work). These damages, called rip and tear costs, are usually enough to overcome this exclusion.

Further, “sudden and accidental physical injury” to the work, after it has been put to its intended use, would be covered, even if it does not physically damage other work and the owner simply loses the use of its building during the repair period. In our example, the leaky roof caused tangible damage to other work and this exclusion would not operate to bar coverage.

What is Suretyship?

Surety is a credit accommodation, not insurance. A surety agrees to answer for the debt of another, is the secondary obligor, and stands behind the debts and obligations of the principal. In the construction context, it ensures contract performance. If a principal cannot secure surety credit, it may have to obtain a bank line of credit or deposit cash collateral in order to satisfy owner demands that it be financially protected from potential contractor default. The principal (and other indemnitors) owes a duty to the surety to perform under the construction contract and, failing that, to indemnify the surety for any losses it incurs due to the principal’s default. Ultimately, the surety retains the ability to recoup losses pursuant to an Agreement of Indemnity, to the extent the indemnitors have the financial wherewithal to pay it back.

Although there are many types of bonds, like fidelity bonds and permit bonds, two types of bonds predominate in the construction industry – payment and performance bonds. Payment Bonds protect third-party subcontractors, laborers and materialmen from nonpayment by the bonded contractor. They also protect the Owner against mechanic’s liens or attested account claims that these lower-tiers could record and pursue in the event of non-payment. The Performance Bond protects the Owner from a Contractor’s inability or refusal to fulfill the terms of the construction contract and/or complete the Project. It is a guarantee from a financial institution that if a principal defaults, its contractual obligations will be fulfilled up to the penal sum or face amount of the bond.

Performance Bond

A performance bond is not insurance. An insurance policy is a contract of indemnity. A performance bond is a guarantee of the performance of the principal’s contractual obligations. A payment bond is a guarantee of payment by the owner to the general contractor, lower-tier contractors, suppliers and materialmen. An insurance policy is issued based on a carrier’s evaluation of risks and fortuitous losses that is actuarially linked to premiums. Losses are expected, but the risk is spread. In contrast, a surety bond is underwritten based on what amounts to a credit evaluation of a particular contractor and its capabilities to perform its contracts. There is an expectation that no losses will occur. A surety usually maintains a close relationship with its contractor-principal as well as the contractor’s bank, accountants and attorneys. As part of the underwriting of bonds, the surety analyzes the strengths and weaknesses of the contractor and its ability to perform its contractual obligations. In short, the underwriting process is very similar to the process used by a lender in making a loan.

A bond is a tripartite relationship. Typically, the parties to a performance bond are the project owner or obligee, the general contractor or principal, and the bonding company or surety.

The performance bond is not for the protection of the purchaser, but rather for the protection of the owner (obligee). If the contractor fails to complete its construction, the surety must satisfy its obligation to the owner under the bond. It does so by: (1) providing additional financing so that the original contractor can complete the work; (2) finding another contractor to complete the construction; or (3) allowing the owner to complete the job itself, with the surety paying the extra cost not to exceed the “penal sum” of the bond.

The surety retains a right of indemnity against the contractor as well as other third-party indemnitors, typically the construction company as well as its owners or principals, individually. In the event of a claim, the surety will invoke the indemnity agreement with its principal (the contractor) and its indemnitors, usually referred to as the General Agreement for Indemnity, to hold it harmless and to defend it against the owner’s claim. Thus, the contractor will, in effect, be required to defend itself and pay the loss from its own funds when it indemnifies the surety. This is the opposite of what happens under a CGL policy. Claims under a CGL are tendered by the policyholder to the carrier and, as is traditional with insurance, the carrier has no right to recoup losses from the policyholder, via subrogation or any other means.

Performance bonds can further be broken down into public and private bonds. Public bonds are statutory and usually referred to as Miller Act (for federal projects) and Little Miller Act (for state and local projects) bonds. As noted, these bonds are statutory and their terms are dictated by statute and cannot be altered, even by agreement of the parties. Private bonds can take many forms. One of the most common is the A312-2010 Payment and Performance Bond.

The Miller Act and Little Miller Acts

The Miller Act is actually a federal statute regulating contractors and surety bonds. It has its origins in a law called the Heard Act. This law was first passed in 1894 and required all contractors to carry a single payment and performance bond to cover losses in case they failed to complete a contracted job.

Unfortunately, the Heard Act was plagued by procedural and substantive limitations, and a more effective law was required. This became the Miller Act, enacted in 1935. The Miller Act provides that for any government contracting or construction job of at least $100,000 (certain exceptions can push this to $150,000), the contractor must carry a payment bond to cover subcontractors and materials providers and a performance bond to allow the government to recoup losses for an unfinished job.

The primary purpose of the Miller Act, however, was to protect subcontractors who supplied material and labor to federal public works projects by providing an alternative and usually superior remedy to the assertion of a mechanic’s lien. Under the Miller Act, a payment bond must be provided by the principal or general contractor on every federal contract to protect the right of payment for those supplying materials or services to the federal project. With few exceptions, all federal public construction projects are subject to the provisions of the Miller Act.

Following the success of the Miller Act for federal projects, the states then began enacting what came to be known as “Little Miller Acts” containing similar requirements for publicly funded state projects. These Little Miller Acts are modeled after the federal Miller Act and state courts have generally held that the Little Miller Acts are to be interpreted in conformity with the federal statute.

Although surety bonds are required by law on most public projects, the use of bonds on privately owned projects is up to each owner. Many private owners require surety bonds from their contractors to protect themselves or their company, lenders and shareholders from the cost of contractor failure. To bond a project, the owner specifies the bonding requirements in the contract documents. Obtaining bonds and delivering them to the owner is usually the responsibility of the prime contractor, who will consult with a surety bond producer. Contractors generally build the cost of the bond into their bids, and the owner thus pays the cost of the bond specified. Subcontractors may also be required to obtain surety bonds to help the prime contractor manage risk, especially when the subcontractor performs a significant part of the job.

Performance Bond Claim Walk-Through

A Performance Bond claim is not triggered by an “occurrence”, like the CGL. Instead, Performance Bonds respond to defaults. An example is probably the best way to explain this process. As noted above, one of the most common performance bond forms is the AIA 312-2010.

This form states:

- 3 If there is no Owner Default under the Construction Contract, the Surety’s obligation under this Bond shall arise after

- the Owner first provides notice to the Contractor and the Surety that the Owner is considering declaring a Contractor Default. Such notice shall indicate whether the Owner is requesting a conference among the Owner, Contractor and Surety to discuss the Contractor’s performance. If the Owner does not request a conference, the Surety may, within five (5) business days after receipt of the Owner’s notice, request such a conference. If the Surety timely requests a conference, the Owner shall attend. Unless the Owner agrees otherwise, any conference requested under this Section 3.1 shall be held within ten (10) business days of the Surety’s receipt of the Owner’s notice. If the Owner, the Contractor and the Surety agree, the Contractor shall be allowed a reasonable time to perform the Construction Contract, but such an agreement shall not waive the Owner’s right, if any, subsequently to declare a Contractor Default;

- the Owner declares a Contractor Default, terminates the Construction Contract and notifies the Surety; and

- the Owner has agreed to pay the Balance of the Contract Price in accordance with the terms of the Construction Contract to the Surety or to a contractor selected to perform the Construction Contract.

According to this form, the Owner must notify both contractor and surety that it is “considering declaring” a contractor default. ¶ 3.1. Next, an Owner may request a meeting, or surety may request one, within five (5) days of notice. The meeting must be held within ten (10) days, unless Owner agrees. Id. The Owner must declare a contractor default and formally terminate contractor’s right to complete the contract. ¶ 3.2. Finally, the Owner must agree to pay the contract balance. ¶ 3.3. The major change between the 1984 version of this form and the current version is that an Owner’s failure to comply with these steps is not automatically fatal to its bond claim. Now, the surety must show actual prejudice flowing from the Owner’s failure to follow these steps.

Apart from the defense that the Obligee failed to follow the terms of the bond and prejudiced the surety, the surety can avail itself of other typical defenses. These include:

- Improper Notice and Opportunity to Cure to Bonded Principal. By way of example, the commonly used AIA A201-2017 § 14.2.2 Termination for Cause requires seven (7) days written notice and opportunity to cure to both contractor and surety.

- Impairment of Collateral. This could stem from improper payments or overpayment to the bonded principal reducing the contract balance or retainage (collateral) that the surety is entitled to recover when the principal defaults. This operates as a release to the extent of the impairment.

- Cardinal Change. This is a material alteration of the underlying contract that was not within the reasonable contemplation of the parties at the time of contracting. The change must be material, rendering the bonded contract new or substantially different, or constitute a breach of the terms of the bonded contract.

- Statute of Limitations / Statute of Repose. The AIA 312-2010 states any claim must be brought within: “two years after a declaration of Contractor Default or within two years after the Contractor ceased working or within two years after the Surety refuses or fails to perform its obligations under this Bond, whichever occurs first.” This two-year suit limitations period is usually shorter than the applicable statute of limitations or statute of repose.

- Standing. The AIA A312-2010 at § 9 states: “No right of action shall accrue on this Bond to any person or entity other than the Owner or its heirs, executors, administrators, successors and assigns.”

Once a valid claim has been made, the surety has options under Article 5. Depending on the circumstances of the default, the surety could finance the defaulted principal and have that company finish the work. ¶ 5.1. The surety could engage a completion contractor to finish the work. ¶ 5.2. The surety could tender a completion contractor to the Obligee. ¶ 5.3. Finally, the surety could pay the Obligee or deny the claim. ¶ 5.4.

Insurance vs. Suretyship – Differences and Overlap

Apart from the differences in how a CGL and Performance Bond respond to a loss/default, the following are other distinctions:

- As noted above, suretyship involves a tri-partite relationship between contractor/ obligor, owner/obligee and bonding company/surety. CGL coverage is a bi-lateral relationship between policyholder and carrier.

- The owner/obligee dictates what performance bond form it will require. Further, the owner has other protections including any held retainage and the contract balance. Finally, the owner has all its contract remedies against the contractor. To the contrary, the insurance carrier dictates the terms of the insurance policy, which is recognized to be a contract of adhesion. As you can see, the policyholder is in a much more vulnerable position vis-a-vis a project owner/obligee.

- A performance bond guarantees contract performance. A CGL protects against claims of fortuitous bodily injury and property damage.

- After a loss, the policyholder tenders its defense and indemnity to the insurance carrier. After a default, the surety tenders its defense to the bonded principal and any other indemnitors.

- The surety can recoup expenditures from the principal and any other signatories under an indemnity agreement. A CGL carrier cannot recoup its losses from the policyholder.

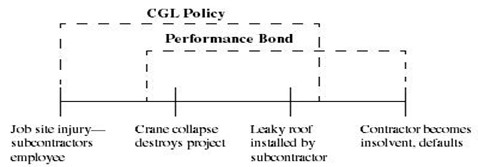

Nevertheless, there is some overlap. As the diagram below illustrates, both a CGL and Performance Bond will respond to certain losses.

Types of Performance Bond Claims / CGL Overlap

Types of Performance Bond Claims / CGL Overlap

Patrick Wielinski, International Risk Management Institute, Inc. (2006).

For losses/defaults that involve only the contractor’s failure to complete the Project, only the Performance Bond will respond because there is no “occurrence” or “property damage” and CGL policies have specifically been held not to provide coverage for purely economic losses.

However, where a loss implicates both: (i) a failure to complete/comply with the terms of the owner/contractor agreement; and (ii) involves “property damage” caused by an accident, both may respond, albeit via the different processes outlined above. For example, claims of warranty work or latent defects, caused by negligent construction oftentimes trigger both the contractor’s CGL policy and Performance Bond. The same is true for the losses flowing from those claims, such as loss of use, financing charges, or liquidated damages (see AIA 312-2010 § 7).