50 Shades of (Grey) Ethics

Am I good person? Deep down, do I even really want to be a good person, or do I only want to seem like a good person so that people (including myself) will approve of me? Is there a difference? How do I ever actually know whether I’m bullshitting myself, morally speaking?

David Foster Wallace, Consider the Lobster and Other Essays

What, indeed, are ethics? We generally understand that ethics, particularly in the legal field, mean those “principles and values, which together with rules of conduct and laws, regulate a profession, such as the legal profession. They act as an important guide to ensure right and proper conduct in the daily practice of the law.”[i] As another source explained, “[e]thics in the courtroom largely boils down to exactly what it is in normal life. Your ethics is your sense of right and wrong, and how you approach situations that technically allow you to do something malicious, harmful, or deceitful.”[ii]

The ethical and moral decisions lawyers must make on a daily basis are mirrored in the choices facing film and television characters. Hollywood has given us example after example of characters presented with complex dilemmas such as whether to compromise their morals for the greater good or which of two evils is lesser. Lawyers, like these characters, must often make tough choices that fall into gray areas – dilemmas where the answer is not a clear right or wrong, yes or no, or black and white. These are areas of “decision-making in which there is no clear consensus on what is ethically right or wrong” and “involve ethical dilemmas that have both pros and cons” where “solutions are difficult to determine.”[iii]

The biggest challenge lawyers often face in these scenarios is that “[i]t is impossible to exhaustively cover concrete reality and action with general rules where the appropriate action clicks out as from a computer. This is as true of farming as of surgery. And of course it is true of ethics.”[iv] While sometimes “what one morally ought or ought not to do is clear,” that is not always the case.[v] As one author explained, that is the case because “[s]ometimes . . . rules have not thoughtfully been provided” and “[s]ometimes . . .the decision is simply beyond the range of reasonable provision of rules.”[vi]

Despite these gray areas, one thing is clear – lawyers must act not only as zealous advocates for their clients but must do so in an ethical manner even when the “ethical” decision is not clear cut or obvious. With that in mind, let’s explore some of the lessons lawyers can learn from Hollywood.

Ethical Lessons from Hollywood

The word “good” has many meanings. For example, if a man were to shoot his grandmother at a range of five hundred yards, I should call him a good shot, but not necessarily a good man.

G.K. Chesterston

- Half Truths and Outright Lies

Searchlight Pictures describes Thank You for Smoking as a “satirical look at today’s culture of spin!”[vii] In other words, the movie’s main character, Nick Naylor, a “charismatic spin-doctor for Big Tobacco” is a liar for the tobacco industry.[viii] As Naylor explains to his son, his “job requires a certain . . . moral flexibility.”[ix] For example, when talking to his son’s elementary school class about his job on career day, Naylor has the following discussion with one of his son’s classmates:

Student: My mommy says smoking kills.

Naylor: Oh, is your mommy a doctor?

Student: No.

Naylor: A scientific researcher of some kind?

Student: No.

Naylor: Well, then she’s hardly a credible expert, is she?[x]

George Costanza: Jerry, just remember, it’s not a lie . . . if you believe it.

Seinfeld, The Beard[xi]

The American Bar Association’s Formal Opinion 508 notes that “[a] lawyer’s role in preparing a witness to testify and providing testimonial guidance is not only an accepted professional function; it is considered an essential component of a lawyer’s advocacy in a matter in which a client or witness will provide testimony.”[xii] Lawyers can violate their ethical obligations in several ways in this situation. First, the outright failure to prepare a witness “would in many situations be classified as an ethical violation.”[xiii] Second, and more relevant to this discussion, [c]ounseling a witness to give false testimony or assisting a witness in offering false testimony,” is a violation of Model Rule 3.4(b).

Jack McCall: Well, I’m a hard case for you, counselor. And make no mistake, everyone in there saw me shoot him.

Lawyer: If you’ll let me set our strategy, I don’t think we’ll dispute what people saw.

Jack: Now, I guess you’re here to break me out.

Lawyer: Son, did James Butler Hickok ever kill a – relative of yours?

Jack: James Butler Hickok?

Lawyer: Wild Bill Hickok. Did he ever kill a brother of yours or – or the like?

Jack: A brother?

Lawyer: I’m asking you if what happened in the saloon was vengeance, for the death of a family member? Possibly a brother in Abilene. Or the like.

Jack: (Smirks, cocks head pensively) A brother in Abilene . . .

(Lawyer smiles, pats Jack twice on the knee, and exits)[xiv]

The “brother in Abilene” is clearly invented by the lawyer to help Jack McCall explain his actions and clearly falls outside the lines of ethical conduct. But what about Nick Naylor’s PR campaign on behalf of big tobacco? What he says in most instances is true and legal, but is his behavior ethical?

Model Rule 3.3 provides that a lawyer “shall not knowingly (1) make a false statement of fact or law to a tribunal or fail to correct a false statement of material fact or law previously made to the tribunal by the lawyer . . . or (3) offer evidence that the lawyer knows to be false.”[xv] In other words, lawyers must be truthful with the Court. Lawyers are not permitted to outright lie or tell half-truths. Doing so, of course, does not mean a lawyer cannot be creative or argue for the interpretation of evidence in a certain light – lawyers, after all, must be staunch and sometimes aggressive advocates for their clients, but they must do so in a truthful and honest way.

- Moral Dilemmas

In The Dark Knight, the Joker, described by Roger Ebert as “a Memphistopheles whose actions are fiendishly designed to pose moral dilemmas for his enemies,” rigs two ferries – one filled with convicts and the other with hardworking, law abiding citizens – with explosives and a detonator for the explosives on the other ship.[xvi] [xvii] The passengers on the two ships are told that the Joker will blow up both boats if one set of passengers does not blow the other boat up before midnight.[xviii] Ultimately, neither set of passengers detonates the explosives on the other ship, notwithstanding attempts by some of the convicts to do so and a vote by the law abiding citizens to detonate the convict-filled boat.[xix]

Lawyers often face moral dilemmas – while it is largely unlikely a lawyer would be called upon to make a decision as to who lives and dies between a “good” person and a “bad” person, lawyers often deal with scenarios that fall into the gray areas of ethics. The Preamble and Scope of the Model Rules of Professional Conduct speak to these situations, noting, among other things:

A. Many of a lawyer’s professional responsibilities are prescribed in the Rules of Professional Conduct, as well as substantive and procedural law. However, a lawyer is also guided by personal conscience and the approbation of professional peers.

B. In the nature of law practice, however, conflicting responsibilities are encountered. Virtually all difficult ethical problems arise from conflict between a lawyer’s responsibilities to clients, to the legal system and to the lawyers’ own interest in remaining an ethical person while earning a satisfactory living.[xx]

There are many occasions when a lawyer’s best interests diverge from those of the lawyer’s client, society as a whole, or others. In those situations, the Preamble and Scope call for lawyers to resolve these conflicts “through the exercise of sensitive professional and moral judgment guided by the basic principles underlying the Rules.”[xxi]

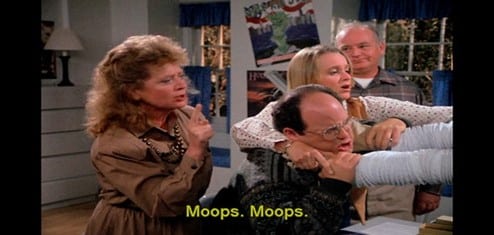

Bubble Boy: Okay, “History.” This is for the game. How ya doin over there? Not too good!

George Costanza: Alright, Bubble Boy. Let’s just play. Who invaded Spain in the 8th Century?

Bubble Boy: That’s a joke. The Moors!

George: Ohhh, no! I’m sorry. It’s the Moops. The correct answer is the Moops!

Seinfeld, The Bubble Boy[xxii]

In The Bubble Boy episode of Seinfeld, George Costanza seizes upon a mistake on a Trivial Pursuit answer card and denies the Bubble Boy a victory for what is clearly the correct answer.[xxiii] Model Rule 3.4 prohibits lawyers from “unlawfully obstructing another party’s access to evidence or unlawfully alter[ing], destroy[ing], or conceal[ing] a document or other material having potential evidentiary value” and from assisting others in doing so.e[xxiv] Rule 4.1 further prohibits lawyers from “mak[ing] a false statement of material fact or law to a third person” and does not allow lawyers to “fail to disclose a material fact to a third person when disclosure is necessary to avoid assisting in a criminal or fraudulent act by a client.”[xxv]

Costanza, faced with what normal people would deem a moral dilemma, chose to take advantage of a mistake by Hasbro. Lawyers do not have that luxury.

- Bending the Ethical Lines

Imagine finding a suitcase full of money in the desert – do you keep it for yourself, turn it in, or keep moving? That is the dilemma facing Llewelyn Moss in No Country for Old Men.[xxvi] Moss chooses to take the money and run, which leads to Moss being pursed by Anton Chigurh, “a preternaturally vicious contract killer hired by the Mexicans to recover the money.”[xxvii] Moss, of course, pays the ultimate price for taking the money – death.[xxviii]

Similarly, in Dumb and Dumber, Lloyd Christmas and his roommate Harry Dunne face the choice of what to do with a briefcase (which turns out to be filled with ransom money) that is “accidentally” left behind by Mary Swanson at an airport.[xxix] Do they keep the briefcase and its contents for themselves, or do they track down its owner, even if it means traveling cross-country to find her?[xxx] Christmas convinces Dunne to help him find Swanson and return the briefcase, telling Dunne that he wants to follow her out west to Aspen: “I’m talkin’ about a place where the beer flows like wine, where the women instinctively flock like the salmon of Capistrano. I’m talkin’ about Aspen,” although Christmas’ desire to make the right decision is dictated by his self-interest in having Swanson fall madly in love with him for returning the briefcase.[xxxi]

Lawyers will not be hunted by Anton Chigurh for blurring ethical lines, but the Model Rules speak to this type of ethics-bending by lawyers in several different areas.

One example can be found in Rule 4.2, which prohibits a lawyer from communicating about a lawsuit with a person “the lawyer knows to be represented by another lawyer” absent consent by the other lawyer or legal authority to do so.[xxxii] Generally speaking, Rule 4.2 provides that lawyers may not communicate with represented litigants, nor may they have others do so on their behalf under Rule 8.4.[xxxiii] But that rule is not always hard and fast, as can be seen in a recent case from Delaware.[xxxiv] In that action, plaintiff’s counsel sent private investigators, posing as potential customers, to speak to lower level employees of the defendant in a patent infringement case.[xxxv] The Court found that under the circumstances, neither Rule 4.1 (truthfulness) nor 4.2 (communicating with represented parties) had been violated.[xxxvi]

Another example centers around the type of closing arguments a lawyer can make. Rule 3.4(e) provides that a lawyer shall not, “in trial, allude to any matter that the lawyer does not reasonably believe is relevant or that will not be supported by admissible evidence, assert personal knowledge of facts in issue except when testifying as a witness, or state a personal opinion as to the justness of a cause, the credibility of a witness, the culpability of a litigant or the guilt or innocence of an accused.”[xxxvii] In sports, coaches preach the concept of “playing until you hear the whistle.”[xxxviii] In addition to encouraging players to be aggressive, part of the idea behind this concept is the notion that it is acceptable to cross the line (for example, to dribble a soccer ball out of bounds) and to continue playing until stopped by an official. Lawyers are often faced with the questions of “where is the line,” “how close can I get to the line,” and “what will happen if I cross the line,” and that is especially true in closing arguments where the facts and/or the law are not always in the client’s favor. Lawyers are left in those instances with resorting to the powers of persuasion.[xxxix]

- The Ends Justify the Means

Oppenheimer “follows the life of J. Robert Oppenheimer, the American theoretical physicist who helped developed the first nuclear weapons during World War II.”[xl] It is well-documented that Oppenheimer was ultimately “guilt-ridden and haunted by the destruction and mass fatalities” caused by his creation, but at the time, the use of atomic weapons was seen as a necessary means to an end of a world war.[xli]

Questions about the ends justifying the means are ones attorneys face on a regular basis. One example can be seen in the context of the unintentional production of information from the other side in litigation. In a recent decision from Washington, an attorney narrowly escaped being disqualified from a case after receiving metadata that should not have been disclosed to her.[xlii] The offending attorney argued, among other things, that the opposing party should not have attempted to redact the information in the first place and that her review of the privileged materials was justified.[xliii]

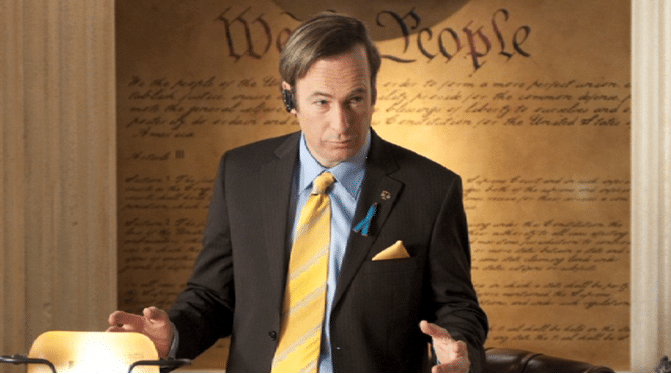

In Better Call Saul, Saul Goodman sets up an elaborate ruse in Court in an effort to convince a jury to find his criminal client not guilty of robbery.[xliv] Goodman has his client sit at the back of the courtroom while another individual who looks very similar to the client sit at counsel table.[xlv] After the store clerk identifies the man at counsel table as the individual who robbed the store, Goodman points out that his client is actually not at counsel table and is, instead, seated elsewhere in the courtroom.[xlvi] As is the case with most of Goodman’s choices as a lawyer, Goodman believes the means justify the ends, commenting to his lawyer-girlfriend Kim Wexler who questions the tactic that he has achieved for his client the “[t]wo sweetest words in the English language . . . ‘miss,’ ‘trial.’”[xlvii]

The idea that the ends justify the means is not entirely consistent in many instances with the Model Rules. The Rules require lawyers to be zealous advocates but at the same time include such limitations as (1) prohibiting a lawyer from representing a new client in a matter similar to one in which the lawyer represented the would-be opponent (Rule 1.9),[xlviii] (2) requiring a lawyer to refrain from bringing or defending an action on a frivolous basis (Rule 3.1),[xlix] and (3) being fair to the opposing party (Rule 3.4).[l]

Navigating the Gray Areas (or: How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Gray Areas)

The following tips might be helpful for lawyers attempting to navigate the dark waters of ethical gray areas:

- Maintain your own sense of ethics

As a starting point, do not “compromise your own natural sense of right and wrong.”[li] Lawyers who do not have their own internal compasses of right and wrong find it “easy . . . to let their morals slip in order to achieve a desirable outcome. Especially when there are no concrete rules against it that will produce serious consequences.”[lii]

- Refer to and follow the rules!

If a lawyer believes he or she is “headed into a gray area or unchartered territory, it’s time to start looking at any relevant laws [the lawyer] can find to ensure [the lawyer is] not doing anything unacceptable.”[liii] In other words, as one source put it, “make sure it’s legal.”[liv]

- Get advice and look at past situations

A lawyer approaching a gray area has an option other than figuring the issue out alone – colleagues, mentors, and peers are great resources for analyzing ethical gray areas.[lv]

- Consider the consequences

The issue with an ethical gray area is not simply “can I engage in this conduct.” A lawyer needs to consider how the behavior may be viewed by the Judge, opposing counsel, and the jury.[lvi] That is true not just in the short term but also the long term.[lvii]

- Develop and implement strategies

As one author noted, “[i]n gray areas, one has to exercise judgment, and judgment is always fallible – which does not mean it is always wrong, and certainly not that it is always irresponsible.”[lviii] One way to combat the fallibility of judgment is to “develop and implement appropriate strategies of judgment that become a constant and reliable element in the practitioners character and life.”[lix] While individuals “can never guarantee that [their] judgments are right, whether in grading papers or in doing brain surgery. But they can guarantee that [they] have done [their] duty, even when [their] judgment was mistaken.”[lx]

- Document decisions

When navigating the gray areas, documenting one’s decisions “can help demonstrate that you acted in good faith and took reasonable steps to comply with the law.”[lxi] Documenting one’s decisions “can also help you defend your actions in the event of legal action or regulatory scrutiny.”[lxii]

[i] https://www.thehorizoninstitute.org/usr/library/documents/main/booklet-on-ethics-for-lawyers.pdf

[ii] https://litiligroup.com/ethics-in-litigation/#:~:text=A%20gray%20area%20might%20start,match%20the%20code%20of%20ethics

[iii] https://www.easyllama.com/definitions/ethical-gray-area/#:~:text=An%20ethical%20gray%20area%20is,solutions%20are%20difficult%20to%20determine

[iv] https://dwillard.org/articles/gray-areas-and-integrity#:~:text=In%20gray%20areas%2C%20one%20has,no%20threat%20to%20moral%20integrity

[v] Id.

[vi] Id.

[vii] https://www.searchlightpictures.com/thankyouforsmoking

[viii] Id.

[ix] https://www.imdb.com/title/tt0427944/quotes/?item=qt3108038

[x] Id.

[xi] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Beard

[xii] https://www.americanbar.org/content/dam/aba/administrative/professional_responsibility/ethics-opinions/aba-formal-opinion-508.pdf

[xiii] Id.

[xiv] Id.

[xv] https://www.americanbar.org/groups/professional_responsibility/publications/model_rules_of_professional_conduct/rule_3_3_candor_toward_the_tribunal/

[xvi] https://www.rogerebert.com/reviews/the-dark-knight-2008

[xvii] https://nerdheaven.podbean.com/e/the-dark-knight-detailed-analysis-review/

[xviii] Id.

[xix] Id.

[xx] https://www.americanbar.org/groups/professional_responsibility/publications/model_rules_of_professional_conduct/model_rules_of_professional_conduct_preamble_scope/

[xxi] Id.

[xxii] https://www.seinfeldscripts.com/TheBubbleBoy.htm

[xxiii] Id.

[xxiv] https://www.americanbar.org/groups/professional_responsibility/publications/model_rules_of_professional_conduct/rule_3_4_fairness_to_opposing_party_counsel/

[xxv] https://www.americanbar.org/groups/professional_responsibility/publications/model_rules_of_professional_conduct/rule_4_1_truthfulness_in_statements_to_others/

[xxvi] https://iwritenoise.medium.com/time-and-chance-a-look-back-at-no-country-for-old-men-35f067a31797

[xxvii] Id.

[xxviii] Id.

[xxix] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Dumb_and_Dumber

[xxx] Id.

[xxxi] https://unofficialnetworks.com/2019/09/16/dumb-dumber-aspen/

[xxxii] https://www.americanbar.org/groups/professional_responsibility/publications/model_rules_of_professional_conduct/rule_4_2_communication_with_person_represented_by_counsel/

[xxxiii] https://www.americanbar.org/groups/professional_responsibility/publications/model_rules_of_professional_conduct/rule_8_4_misconduct/

[xxxiv] Impossible Foods, Inc. v. Motif Foodworks, Inc., 675 F.Supp.3d 448 (D.Del. 2023)

[xxxv] Id.

[xxxvi] Id.

[xxxvii] https://www.americanbar.org/groups/professional_responsibility/publications/model_rules_of_professional_conduct/rule_3_4_fairness_to_opposing_party_counsel/

[xxxviii] https://btr.michaelkwan.com/2011/09/20/dont-stop-playing-until-you-hear-the-whistle/

[xxxix] https://www.alfainternational.com/wp-content/uploads/Closing-Argument-Ethos-and-Ethics.pdf

[xl] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Oppenheimer_(film)

[xli] Id.

[xlii] Hur v. Lloyd & Williams, LLC, 25 Wash.App.2d 644 (Ct.App.Wash. 2023)

[xliii] Id.

[xliv] https://tvshowtranscripts.ourboard.org/viewtopic.php?f=205&t=37260

[xlv] Id.

[xlvi] Id.

[xlvii] Id.

[xlviii] https://www.americanbar.org/groups/professional_responsibility/publications/model_rules_of_professional_conduct/rule_1_9_duties_of_former_clients/

[xlix] https://www.americanbar.org/groups/professional_responsibility/publications/model_rules_of_professional_conduct/rule_3_1_meritorious_claims_contentions/

[l] https://www.americanbar.org/groups/professional_responsibility/publications/model_rules_of_professional_conduct/rule_3_4_fairness_to_opposing_party_counsel/

[li] https://litiligroup.com/ethics-in-litigation/#:~:text=A%20gray%20area%20might%20start,match%20the%20code%20of%20ethics

[lii] Id.

[liii] Id.

[liv] https://www.easyllama.com/chapter/ethical-gray-areas/

[lv] https://litiligroup.com/ethics-in-litigation/#:~:text=A%20gray%20area%20might%20start,match%20the%20code%20of%20ethics

[lvi] Id.

[lvii] https://fastercapital.com/content/Exploring-the-Legal-Gray-Areas–Unveiling-Loopholes-in-the-System.html

[lviii] https://dwillard.org/articles/gray-areas-and-integrity#:~:text=In%20gray%20areas%2C%20one%20has,no%20threat%20to%20moral%20integrity

[lix] Id.

[lx] Id.

[lxi] https://fastercapital.com/content/Exploring-the-Legal-Gray-Areas–Unveiling-Loopholes-in-the-System.html

[lxii] Id.